Insights from the Centre for Analysis of the Radical Right’s Inaugural Conference in London

In May of 2019 Tech Against Terrorism attended the inaugural annual conference of the Centre for Analysis of the Radical Right (CARR) - the leading...

5 min read

Claudia Wagner Sep 2, 2019 1:06:45 PM

Open-source software (OSS) is a type of computer software in which the source code is released under an open-source license. Any programmer can release software under an open-source license which grants users the right to view, change and even redistribute the software to anyone and for any purpose. Much of this is managed by services such as GitHub and BitBucket.

A large amount of today’s technology is underpinned by open-source licensed code. In some cases, technology is entirely based on open-source, such as most web server technologies, whereas some software partially deploys open-source for some elements. For example the operating system that powers Apple Mac for example partly depends on open-source code. If open-source software disappeared, the whole tech infrastructure including a broad array of software products would break. This is exactly what happened in 2016 when a developer unpublished only 11 lines of his code and disrupted the whole web development industry.

The inherently open nature of open-source benefits everyone, encouraging global collaboration for the greater good. However despite the clear advantages of open-source, its inherently open nature also attracts terrorists and violent extremists. We believe that the current debate around terrorist and violent extremist use of the internet must be broadened to include a much-needed discussion about the decentralised web and open-source licenses, its abuse by various entities, and appropriate human rights compliant measures to prevent this from happening whilst keeping the open-source spirit alive.

Terrorist and (violent) extremists are increasingly using open-source software to facilitate the spread of terrorist and hateful material online. This raises concerns about the impact of giving users the right to use and extend open-source products.

On July 4, 2019, Gab – a social media platform that predominantly attracts alt-right users, conspiracy theorists and other trolls but has also been used by terrorists, such as the Pittsburgh shooter – announced an updated version of its platform. Its developers forked the source code of Mastodon, a free open source and decentralised social network, making Gab now a decentralised platform and considerably more resistant to content moderation efforts. In addition, Gab is now also available on mobile phones through their own app store.

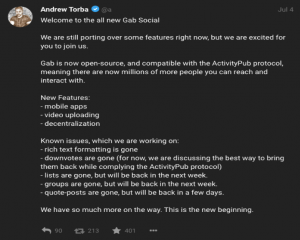

The ‘all new Gab Social’ as CEO Andrew Torba called it is open-source and compatible with ActivityPub, a standardised communications protocol for decentralised networks, making decentralisation one of Gab’s main features (Fig.1).

Figure 1: Gab CEO announces new version on 4 Jul 2019

Figure 1: Gab CEO announces new version on 4 Jul 2019

Decentralised networks are very similar to the web we know, but the main difference lies in the “middle man”. To communicate within a decentralised network, users do not rely on a central node or server in the network. Most importantly, decentralisation reverses the current data ownership model by empowering users who will instead have full control over their data.

On Twitter, for example, users rely on Twitter’s servers for hosting, sending and receiving content. Twitter also has the power to remove tweets and suspend or ban accounts that violate their terms of service. With decentralised social networks, however, this would no longer be possible as the content would be spread across the network and not stored in one centralised location.

Mastodon is a Twitter-like decentralised microblogging platform; however, anyone can take a copy of the source code with which developers can create their own decentralised social network. On Mastodon, they are commonly referred to as an ‘instance’.

Much like Twitter, users can create profiles, follow other users, and post messages. A tweet is called a "toot", a retweet is a "boost", and the character limit is 500 instead of Twitter's 280.

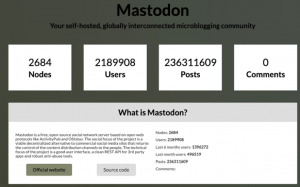

With Mastodon, it is the ‘instance’ owner who decides what is acceptable and what is not, thus empowering them to set their own community guidelines. There are currently 2684 active instances, with over 2.19 million users worldwide (Fig.2).

Figure 2: Current statistics. Source: https://the-federation.info/mastodon

Figure 2: Current statistics. Source: https://the-federation.info/mastodon

Users within an instance can follow and communicate with each other. The same is possible when users want to follow and communicate with users of other instances. Instances are privately operated and moderated. What makes Mastodon a decentralised network is that users from instances can not only communicate with each other but also with other instances and their users (Fig.3).

Figure 3: Mastodon - decentralised communication

Figure 3: Mastodon - decentralised communication

Another key feature which needs to be emphasised in this context is that Mastodon (and decentralised networks in general) “can’t go bankrupt, can’t be sold and can’t be completely blocked by governments”.

Open-source rests on the notion that the more people are involved, the more ideas and innovation can flow into the end product, which consequently benefits the product and subsequently the whole community.

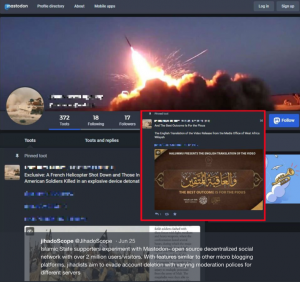

Open-source licenses allow anyone to use, modify and share the code. This includes (as with Gab) those that “welcome users banned or suspended from other social networks”. Gab is not the only example; Jihadoscope recently discovered Islamic State (ISIS) supporters experimenting with Mastodon (Fig.4). This further underlines the argument that open-source software is inherently available to anyone, including terrorists.

Figure 4: Screenshot by Jihadoscope

Figure 4: Screenshot by Jihadoscope

Every open source license has to comply with the “Open Source Definition", originally derived from the Debian Free Software Guidelines, which set out 10 criteria that any license agreement needs to comply with. Nevertheless, none of these call for a prohibition of the open source product being used against particular individuals or groups.

Developing appropriate and widely accepted countermeasures to curb terrorist and violent extremist use of open-source products is exceptionally challenging and requires extensive discussion between tech experts, policymakers, civil society and others. But in essence, any countermeasure needs to strike the right balance between being human rights-compliant and maintaining the open-source spirit - a key driver for innovation.

When talking about terrorist and violent extremist use of the Internet, academics, practitioners and policymakers now have to take these issues more seriously. As demonstrated in our previous analysis, ISIS has already carried out experiments on the decentralised web - it’s only a matter of time until DWeb applications become more user-friendly and widely accepted. Therefore, we must start a serious discussion about the abuse of the DWeb, and appropriate responses to counter these efforts.

The current debate around terrorist and violent extremist use of the Internet should be broadened to include a much-needed discussion about the decentralised web and open source licenses, its abuse by various entities, and appropriate human rights-compliant measures to prevent this from happening.

The case of Gab is an illustrative example of how decentralisation and open source-software can be combined to build a takedown-resistant platform that houses violent extremist speech. Professor Matthew Feldman, director at the Center for the Analysis of the Radical Right (CARR), recently told Scram news: “Digital technology offers the radical right three things it has long coveted: potential anonymity [...] a transnational, global reach and permanent visibility of message.”

It is not only the radical right that aspires to make use of decentralised platforms. ISIS, for instance, has been long keen on finding a viable alternative to Telegram and in theory, they could follow the same path as Gab has done in building a take-down resistant platform by forking open source-code(s).

In May of 2019 Tech Against Terrorism attended the inaugural annual conference of the Centre for Analysis of the Radical Right (CARR) - the leading...

Our weekly review of articles on terrorist and violent extremist use of the internet, counterterrorism, digital rights, and tech policy.

1 min read

Our weekly review of articles on terrorist and violent extremist use of the internet, counterterrorism, digital rights, and tech policy. -Terrorist...