Analysis: The use of open-source software by terrorists and violent extremists

Why global coding collaboration benefits everyone – including terrorists and violent extremists.

7 min read

Claudia Wagner Jun 6, 2019 12:59:14 PM

In May of 2019 Tech Against Terrorism attended the inaugural annual conference of the Centre for Analysis of the Radical Right (CARR) - the leading information aggregator and knowledge repository on the radical right. The conference saw more than 50 different presentations from leading academics and practitioners in the field. In this post we share our insights and recommendations which will help us guide our ongoing work on far-right terrorist use of the Internet.

Tech Against Terrorism focusses on all types of violent extremist and terrorist use of the Internet, including far-right violent extremism and terrorism. Given that this conference covered the far-right generally, some presentations discussed both violent extremist and non-violent strands of the wider global far-right, and we have attempted to make this distinction clear throughout the text. This post is a summary of what was presented and does not necessarily reflect the views of Tech Against Terrorism.

Based on our findings at the CARR conference, we recommend the following:

Below are the key insights identified during the conference:

Based on the presentations at the conference, there is a general academic consensus that the global far-right, including the violent extremist far-right, is growing. Two specific causes behind this were offered by several presenters during the conference.

Mainstreaming of far-right political discourse

Many speakers warned against the mainstreaming of far-right political discourse. In her keynote speech, the United Kingdom’s Lead Commissioner for Countering Extremism Sara Khan noted how this is visible in how racist discourse has entered UK public debate, noting specific concern over anti-Muslim language. Mark Potok, formerly of the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC), noted a similar development in the United States.

However, this development is not only due to the mainstream adopting far-right positions, but as Cynthia Miller-Idriss noted also the result of active efforts by extremists to mainstream their message. Such efforts include the adoption of populist rather than extremist language, mainstreaming of extremist imagery, and deliberate efforts to bring conspiracy theories into the public debate.

Transnational links

That the global violent extremist far-right is transnational in its connections and operations is not new. However this inter-connectivity has been made apparent from investigations into dissemination of violent extremist far-right and white nationalist publications, the role played by European neo-Nazis in organising the 2017 Charlottesville protests, and the usage of transnational extremist symbolism by the Christchurch mosque terrorist. This is visible in the online space, as stressed by Julia Ebner who noted that there is an online nexus of heterogeneous violent extremist far-right players which is becoming increasingly connected via social networks.

From the CARR conference, there are several conclusions with regards to how far-right violent extremists and terrorists use technology and Internet platforms.

One key conclusion is that far-right violent extremists operate both within a mainstream tech ecosystem, consisting of larger open platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube, in addition to a slightly separated ‘alt-tech’ eco-system. This consists mainly of sites which replicate many of the functions offered by mainstream social media platforms but have been created for (or co-opted by) a far-right audience. Examples of this include sites like Gab, Voat, Minds, and 8chan, but also crowd-funding sites like Hatreon, WeSearchr, and GoyFundMe. The creation of such ‘clones’ has largely been spurred by de-platforming of prominent far-right actors and other disruptive efforts by larger tech companies.

Similar to Islamist terrorist use of the Internet, several platforms are used in tandem throughout recruitment and radicalisation processes. Julia Ebner demonstrated that recruitment and mobilisation often occur on open platforms like 4chan and 8chan, radicalisation and coordination takes place on end-to-end encrypted messaging platforms such as Telegram and WhatsApp, before attempts to mainstream the message occur on larger social media platforms like Facebook.

This reflects Tech Against Terrorism’s argument that any research into terrorist use of the Internet needs to analyse why actors choose certain platforms and the various uses (strategic vs operational) they offer. In our research into far-right violent extremist use of Telegram, we have noted that many of these groups and channels are more user-friendly compared to the jihadist groups we research. One example of this is the use of comment bots by some violent extremist far-right channels, allowing users to easily view and join discussion threads for individual posts rather than commenting straight into the channel itself. Until now, the violent extremist far-right has generally faced less disruptive efforts by Telegram than jihadist terrorist groups which has allowed for such tweaking and optimisation.

Lastly, far-right violent extremists are highly attuned to online culture and have, in many ways, created its own online culture. Ebner highlighted how far-right online rhetoric is based on gamification and transgression, often manifested in jokes and memes. This was apparent in the Christchurch attack and the virality-bound online content that the perpetrator shared, which made references to both video games and popular far-right memes. Emilie de Keulenaar and Marc Tuters both demonstrated how this is manifested within spaces like 8chan. These cultures reward fringe extremist content and knowledge of established in-group jargon. Such processes inevitably facilitate the emergence of ‘echo-chambers’ in which opposing narratives are difficult to get across.

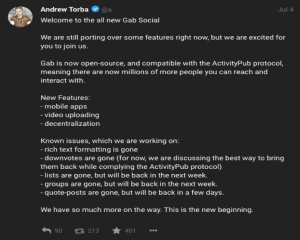

Despite challenges faced by far-right violent extremists due to disruptive efforts on surface-level platforms, the alt-tech space noted above has provided the movement with enough stability to sustain its online operations. This might change in the near future. As noted by Brian Hughes, within the past few months there has been a substantial increase in disruptive efforts on the infrastructure level, including web hosting services and Domain Name Server (DNS) registrars. The most notable example of this was when Gab’s DNS registrar (GoDaddy) and web hosting service (Joyent) terminated their collaboration with Gab following the October 2018 Pittsburgh synagogue shooting.

According to Hughes, there are two likely implications of this. Firstly, similar to how the wider far-right created alternative social media platforms on the surface-level, we are seeing an increase in ‘alt-infrastructure’ platforms. One such example is Epik, a web hosting service hosting Gab, following its expulsion from Joyent, and BitChute, a video-hosting site with a demonstrated presence of far-right violent extremist and terrorist material. In our investigation into tech company responses to the Christchurch, New Zealand terrorist attack, we found that BitChute had not removed the attack footage from its site. At the time of writing, the video was still accessible on the platform. Another example of an alt-infrastructure company is NT Technologies, a company based in the Philippines currently hosting 8chan.

However, the fact that violent extremist and terrorist content exists on platforms supported by alt-infrastructure makes ensuring financial sustainability difficult, since it severely diminishes possible ad sales. This leads us to the second implication highlighted by Hughes. As a result of the financing and disruption issues, we are likely to see a larger migration to the Dark Web. This is because the Dark Web would allow for evading some of the challenges faced by the violent extremist far-right on the traditional web, for example through the usage of peer-to-peer hosting to prevent takedowns and crypto-mining for self-financing.

When assessing where far-right violent extremists and terrorists might go next, it might be worth looking at where ISIS has already gone. As outlined in one of our recent posts, the decentralised web hosts a lot of potential for terrorist groups although it has to date not become its preferred arena. Far-right violent extremists and terrorists have looked to ISIS in the past, as exemplified in their increased use of Telegram, so it is not surprising that they are keeping an eye on how the experiments with the decentralised web are progressing.

As demonstrated during the conference, there is important research being carried out on this topic, but compared to the plethora of research studying jihadist terrorist online activities the issue of far-right violent extremist and terrorist use of the Internet remains understudied. At Tech Against Terrorism we will aim to contribute to this body of research over the coming months.

It is crucial that all future research of far-right violent extremism online applies the academic rigour on display during the CARR conference. As stressed by Cynthia Miller-Idriss, we need to study the spaces which allow for radicalisation - not only ‘how’ and ‘why’ an individual is radicalised. By increasing our understanding of online spaces’ role in this dynamic, we can more strategically engage in any counter-measures targeting far-right radicalisation.

Furthermore, there is an urgent need for definitions and distinctions. As noted by Cas Mudde, the ‘far-right’ remains a wide and somewhat unhelpful term that bundles together populist movements with groups or individuals engaging in terrorist activities. Part of the success with tackling jihadist online content is directly due to the fact that there is consensus around what jihadist terrorism is and which groups this includes. Clearer definitions of far-right terrorism and designations of groups and individuals engaging in terrorism will help tech companies take action on such content.

The above action areas will facilitate the upscaling of appropriate support for tech companies to identify, assess, and tackle far-right terrorism on their platforms. Support for tech companies, and primarily smaller tech companies, needs to be practical and allow for companies to tackle terrorist exploitation whilst respecting human rights. This latter factor is especially important so to not accidentally feed the wider far-right narrative that mainstream media and tech platforms are ‘suppressing’ their views. At Tech Against Terrorism, we will continue to develop practical tools for companies to tackle far-right violent extremist and terrorist use of the Internet.

Why global coding collaboration benefits everyone – including terrorists and violent extremists.

Tech Against Terrorism Reader's Digest 21 February 2020 Our weekly review of articles on terrorist and violent extremist use of the Internet,...

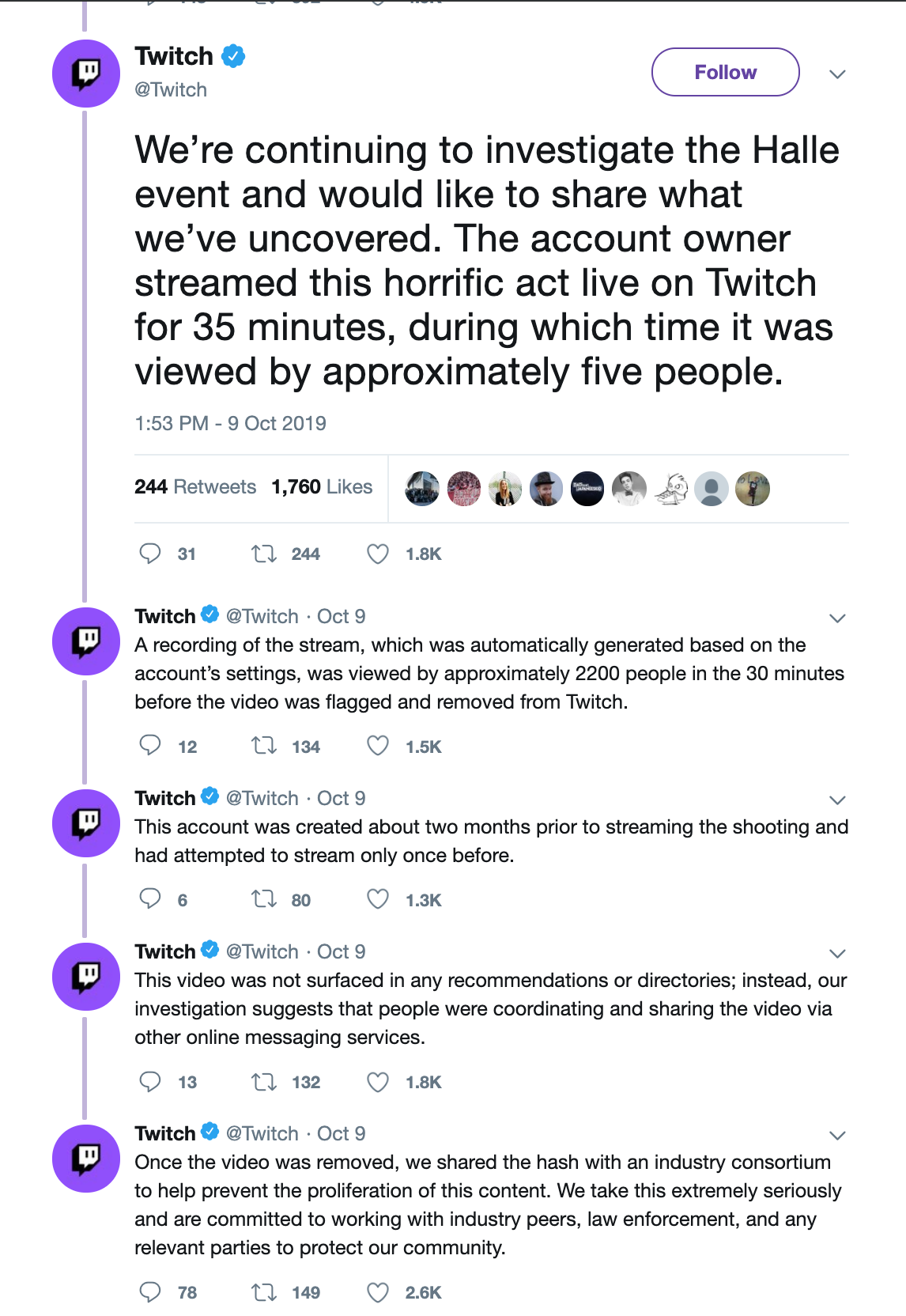

Below we summarise tech sector responses to the use of their services by the Halle terrorist and sympathisers in the wake of the attack on 9 Oct 2019.